More than the crisis of crime and violence, the Brazilian favelas suffer from a chronic lack of representation and community solidarity. The nature of the precarious existence of the subaltern in the favelas of Brazil shows us that the favela residents exist in a space that is devoid of government. Most of the favela residents didn’t have access to the structures of citizenship and they live under constant threats to their lives.

The street children are brought up in a system of oppression where their destiny is bound by their origins. Coming from these origins, the only means for one to exist in the governed space is to reduce themselves to a performance of existence and create a narrative that can be accepted by the civil society.

The street children are brought up in a system of oppression where their destiny is bound by their origins.

Coming from these origins, the only means for one to exist in the governed space is to reduce themselves to a performance of existence and create a narrative that can be accepted by the civil society.

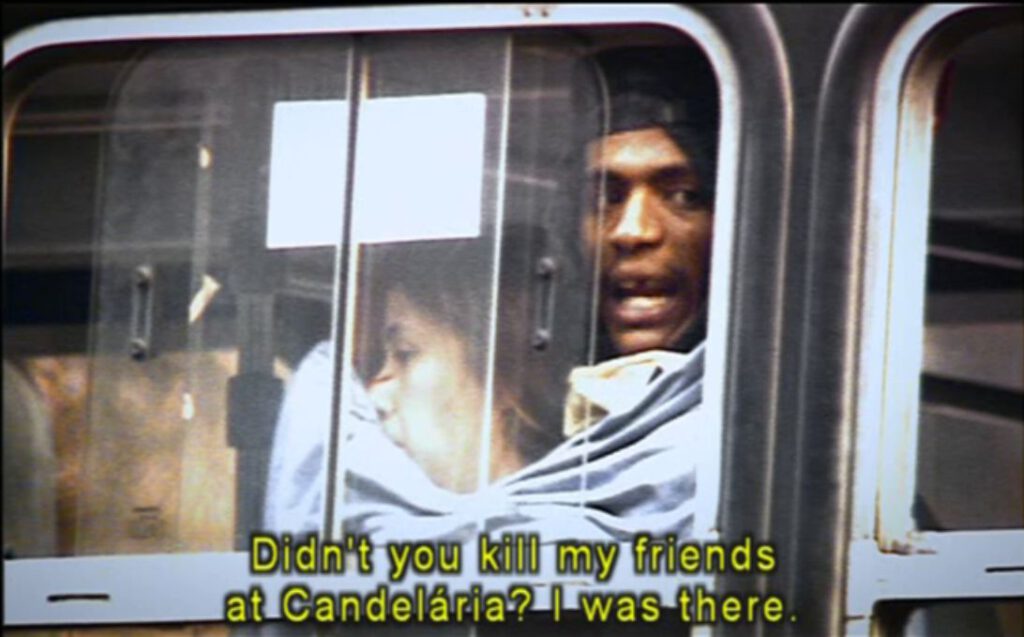

We see how Sandro in Bus 174 repeatedly refers to film scenes and how the street children perform on traffic stops. But even when the performance is able to attract the attention of the citizens, it cannot elucidate them as human subjects. The citizens stuck in traffic treat the children with indifference and Sandro is suffocated to death. Therefore, the speech-act of Sandro and the children of the favela seem to be lost on the citizens of Rio.

The lost voices of the street children signifies the highest point of desperation of the lives of the urban poor of Brazil.

The dream of the rural-urban migrants of social mobility afflicted by the government’s lack of action for providing them with basic civil amenities have lead to a destitute regression to desperation in many of the favelas. For the urban poor of Brazil, the crisis of poverty comes doubly marred with a sense of implausibility of improvement and an easy path to success through crime. Especially for the young kids in the favelas, who apparently suffer from the delusion of personal fable, the latter seem as the obvious preferable choice.

While many are deterred due to the very practical risks of the criminal life, the risk factor becomes the primary selling point of the “gangsta” life for many other. The hoodlums of the favelas become the symbol of power and prosperity for the kids. Even for kids who are too afraid to join the gangs in the beginning soon toy with the idea of getting involved when they see how difficult it is for them to prosper through honest means.

The power status of the criminal activities and the implausibility of an honest living combine to create a recipe for violence that sucks the kids of the favela into a life of crime.

A big reason for this phenomenon is also the denigration of the sense of solidarity within the communities. Afro-Brazilian communities like the Quilombos have found ways to keep their cultural values and social solidarity intact through many years of oppression and government neglect, but the migrants fail to do so due to the individualistic nature of urban success model. As such, societies regress to nuclear families and desolate individuals who fail to empathize with the other and thereby lose command or influence over the lives of the children.

The children neglect their parents commands because they think that success lies elsewhere than the parental dictum.

The children neglect their parents commands because they think that success lies elsewhere than the parental dictums. The parents find themselves in an even harsher condition when they reach an old age as they are left to fend for their own, even in societies of affluence. Therefore, the urban ideal of individualistic success seeps into the minds of the children so much that they look for ways to maximize their own gain without an assessment of the social costs or the costs to the lives of others. As personal fable allows the kids to choose a life of danger for themselves, they care little about the trauma to their family in case of their death.

On the other hand, we see that the rural societies succeed in developing a stronger sense of solidarity among themselves through their own traditional religious and cultural practices where the society is broader than one’s nuclear family. The Quilombolas have been able to develop their own indigenous institutions that are designed to preserved their cultural heritage and group integrity.

The group music and dances have been developed in a way that fosters a sense of community and mutual responsibility among the community members. The mainstream has termed them a “cult” because it is already intimidated by the level of solidarity the Quilomobolas have achieve through their methods of worship and prayer. The Quilombolas are able to endure any sort of intrusion from the outside through the institutions they have built on the inside. But such institutions fail to develop in the favelas. The aspiration for development in the favelas gives a rise of desperation among the residents and children who are not afraid to resort to violence or crime when necessary. In these circumstances, the new children of the favela fail to find positive role models and get involved with violence in an early age.

However, grassroots movements to revert this trend is underway through the religious and cultural groups. there is a distinctiveness in the way that the marginalized have learned to perceive and interact with their world which is not accepted in the mainstream. Capoeira and Candomble have become new sources of spiritual and communal redirection in these communities. If the universities and other urban institutions open up more to the children of the favelas, the problem may be solved to some extent.

If the Black independent communities can create such a powerful space for themselves as well through their cultural activities, it is possible for them to keep their cultural integrity intact while getting included into the mainstream society. I think that introducing the children of the favela to other types of methods for expressing their emotions could be helpful in controlling violent outbursts as well as criminal activities.

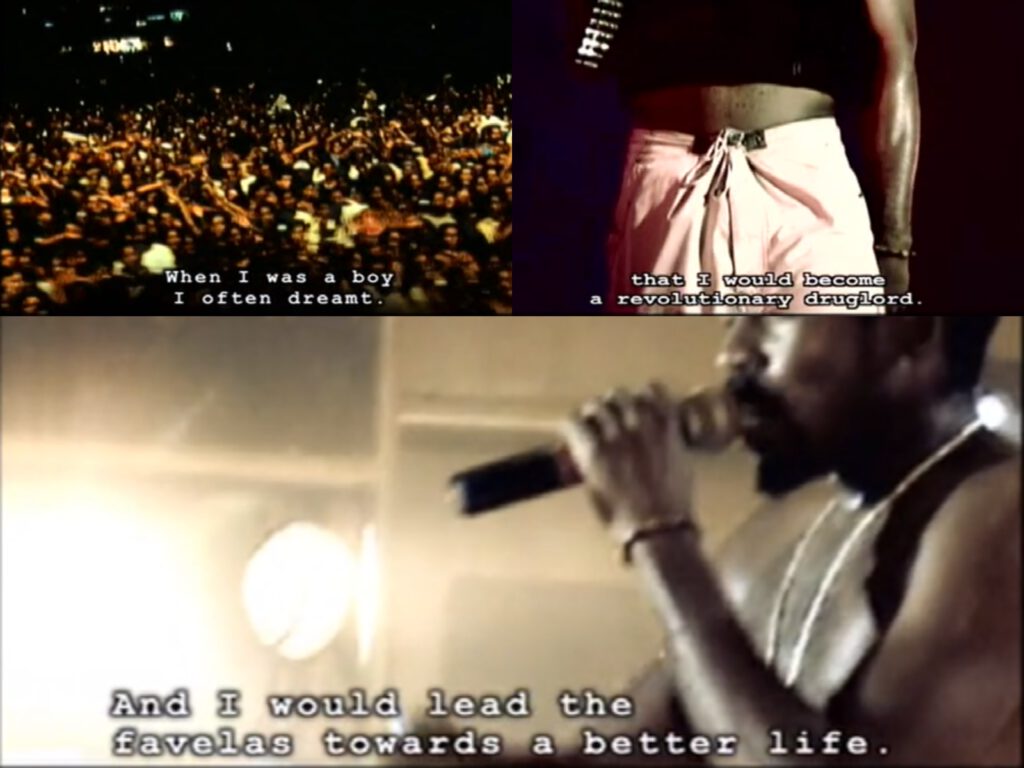

Some of the examples are funk music, samba, rap and Capoeira. The AfroReggae group in favela rising was the epitome of this expression. One of the group members even mentions Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and creation and says that the group members are doing something similar with their art. I think that this image of rising from the ashes like a Phoenix or using the pain to create could bear a strong resonance in the minds of the children of the favela. We see that the children are joyously participating in the training drum lessons of Afro Reggae. I think that these activities are definitely very strong defense mechanisms, but at the same time, they also operate as languages. Also, art can even transcend that and enter the sphere of worldview.

At one point, culture becomes a part of the world and a tool to build the world. And a world built by music is much better than a world built by violence.

In many cases, these movements borrow elements from the rural and Afro-Brazilian roots of the Quilombos. Also, the actors and actresses have tried to create positive role models who are integrated into the urban middle-class lifestyle. To some extent, these steps have contributed to the generation of a counter-narrative in the favelas.

However, this process of cultural reconstruction needs to be slow, deliberate and careful.

Cultural integrity should be a primary concern in terms of social inclusion. The steps that need to be taken to ensure this cannot come from the above. They need to be organic and they need to originate from the people of the community. If the people in the community engage in a retelling of their story like the director of the Summer of Gods did, they can create a space for themselves within the cultural fabric of Brazil. That is how Afro-Brazilians will not only make their space into the Brazilian culture, but fundamentally change it into an inclusive space where all are free to use the culture to express the stories of their community. If the Black independent communities can create such a powerful space for themselves as well through their cultural activities, it is possible for them to keep their cultural integrity intact while getting included into the mainstream society.

Anupam Debashis Roy is a Bangladeshi writer, speaker and activist. He is the Editor of Muktiforum. Find out more about him here.